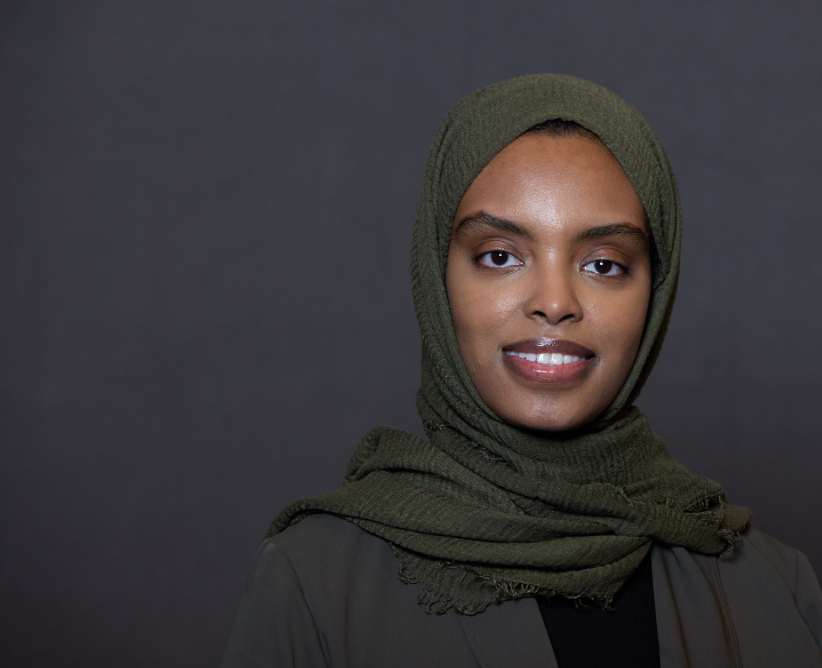

Hayat Omar, is currently completing her second undergraduate degree with the University of Ottawa, currently studying International Development and Globalization she is interested in development, policy, and management. Hayat interned as a Project Support Officer with the Ethiopia team, as well as with HQ. In the past, she has interned and worked with various NGO’s, non-profits, as well as in the public sector. She is invested in African development issues and hopes to work within the continent in the future.

Africa is a continent which has been plagued by internal conflict and violence. Violence has increasingly become the mechanism through which actors implement change, attempt to alter the harsh realities of their lives, and challenge and governments and power structures. Much of Africa continues to face income inequality, inadequate health resources, infrastructure, and employment opportunities. Moreover, these issues have persisted for decades, fomenting a context in which aggrieved peoples and communities conclude that violence (on a progressive spectrum from low-level crime, to violent protests, and eventually organized coup d’états) is the only means through which meaningful change can be achieved. Scholars and analysts define this as ‘revolutionary violence’. Many of the crimes and conflicts actioned by Africans are attributed to “…overlapping injustice that betrays the basic presuppositions of a democratic state” (Chandoke 2015). Violence in this case has been defined as; “…brutality of predators and of hapless victims, of savage violations of the body and damage to the mind…” (2015). In this context, the epitome of the expression of revolutionary violence against the state is the coup d’état.

In the last decade, Africa has experienced an uptick in the number of coup attempts (Observe Research Foundation 2021). In October 2021, the UN Secretary General António Guterres also warned of ‘an epidemic’ of coups after the military takeover in Sudan (Reuters 2021). Although there was a slight decrease in instances of this form of revolutionary violence in the initial decade following the end of the Cold War, more recently the frequency of coup d’états has increased once again. Uniquely, “[C]oup-related repression, including explicit allegations of unrealized coup plots, is less frequent in democracies” (Bell 1169). For this reason, democratic governance models and their associated institutions have been identified as mechanism that can reduce the likelihood of political violence. Federalism, as a model which is predicated on the concept of ‘self-rule and shared-rule’, has been viewed as a form of state architecture particularly suited for acoomodating the diversity that characterizes many of the nations of the post-colonial continent. A handful of African states, such as Nigeria, Ethiopia and South Africa, have adopted and implemented federal governance models, with mixed and sometimes unfortunate results. Gebeye describes federalism in Africa as a means “…to regulate and manage [countries’] internal political dynamics… as a holding together device, federalism in Africa enshrines unique normative and institutional configurations” (12-13). Hence, federal principles have been applied to the political settlement as a means of governing, with an implicit agenda of meeting the demands of groups characterised by ethnicity, religion, language or other facets of identity. For instance, in Ethiopia, federalism has been employed as a democratic governance model that recognizes ethnicity as an identity marker for different groups within the territorial boundaries of the state. However, the inadequate implementation of the federal model has resulted in division and interstate conflict. But despite the uneven results of federalism in African nations to date, federal models and decentralization remain part of the solution to accommodating and recognizing diversity. If countries in the continent are to reduce their vulnerability to destabilizing revolutionary violence, which inhibits development and damages communities, it will require political leaders and political elites to:

- refrain from taking advantage of their power;

- avoid using division as a means of governance;

- engage in transfer of powers to lower levels to enable power-sharing.

The case of Sudan – a country which under the October 2020 Juba Peace Agreement will be established as an asymmetric federation – will be used to illustrate the importance of these dynamics to achieving greater peace, stability and development across the African continent.

Power Imbalance

One of the factors that has contributed to limiting the potential and positive outcomes of federalism for Africans is the inability for African leaders to relinquish political power once it has been secured. This is not a novel observation – many have identified that African leaders often have the mentality and intention to remain in power for multiple terms, regardless of the constitutional or ethical validity of doing so, such as Biya, and Museveni (Brookings Institute) to name a few. This often leads to highly centralized dynastic politics centred on a single leader or party, which runs counter to the federal principle of power sharing between majority and minority groups to enable all to protect and pursue their interests. Many African countries, such as Sudan, have failed to undertake a democratic transfer of powers and competences from highly centralized governance institutions often dominated by a small group of elite leaders, to more decentralized structures which enable all groups within the state to exercise a degree of decision making autonomy over their own lives. In numerous cases, incumbents have flagrantly revised or amended national constitutions in order to extend and prolong their terms in office, such as Presidents Gnassingbé of Togo, and Egypt’s President el-Sisi. This has been defined as a constitutional coup (Brookings Institute).

Most recently, in Sudanese politics, after nearly three decades in power, the government of Omar al-Bashir was overthrown by a military coup d’état in April 2019. This occurred after a questionable period in office for the al-Bashir. Following his rise to power in a bloodless military coup in 1989, al-Bashir undertook a top-down Islamization of Sudan, accompanied by a strict adherence to Sharia law, which alienated and repressed non-Arab and non-Muslim communities in the country (Robbins and Rubin) and made Sudan a breeding ground for Islamic extremists and fundamentalists around the world (Kostelyanets 95). Al-Bashir made several other contentious decisions during his time as president, such as “…sending Arab militias to the Darfur conflict… the separation between the North and South… increase in media censorship… and increase in number of taxes” 97-98) that ultimately led to public dissatisfaction in his regime. The violence that ensued prior to and after the regime change continues to have an impact on the country’s transition to democracy today and manifested itself in the overthrowing of Al-Bashir’s rival and successor Abdalla Hamdok in October 2021.

Governing with Ethnic and Religious Divisions

Federalism as a governance model should have clear and straightforward implications. In practice this has not always been the case in the implementation of federal systems. Federalism in Africa has a history of being typically associated as an “institutional framework for ethnonational and religious” (Gebeye 10) state organization. In addition, “…in Africa, one of the most important constraints to democratic consolidation is the violent struggle by various factions, many of which are actually ethnocultural” (Brookings Institute). In comparison to classical federalist theory, which broadly argues that federalism is a governance model that brings diverse groups together within a single state while allowing for various degrees of self-determination, some African politicians have used federalism to sow greater division amongst the population. In sum, “ while federalism in Africa shares the forms, structures, and discursive practices from classic federal theory, its normative articulations and institutional frameworks are animated by syncretic configurations” (Gebeye 1).

This has been reflected in Sudanese politics, where in the past (notably in the pre-partition 2005-2011 period) an attempt has been made to cultivate democratic principles and institutions through a form of ‘Islamic federalism’, with little success. The use of differences in culture and religious beliefs for political ends has caused internal divisions to expand across North and South Sudan resulting in a form of exploitation. As Sharia law is the fundamental basis for the country’s legal system and state law, those groups in the country who do not share Islamic beliefs feel marginalized. “Islamization spread from above to all spheres of life…meanwhile the fires of the rebellion in the South reignited, as Christian and animist population saw the introduction of Sharia as a break with previously reached agreements” (Kostelyanets 93). The use of religion as tool to govern has enhanced the divisions among religious minorities in Sudan. In the context of the foundations of classical federalist theory, Sudanese federalism has been misapplied in the past, excluding the decentralizing of power and competences to minority groups, . Ultimately, Sudan’s previous attempt at establishing federalism was unsuccessful because its framework was built on division rather than self- and shared-rule.

Inadequate Constitution and Judicial Processes

Federalism is not a one-size-fits all solution to the inequality, political violence and inter-group conflict that has made Africa the epicentre of coups in recent years. It does, however, provide a means through which transitional democratic states can adopt and develop an institutional framework that encourages a peaceful, inclusive and pluralistic society. These democratically weak states, have “…accepted democracy in theory, but in reality, they are semi-democratic… They have accepted democracy, but democratic principles of freedom of speech, human rights, free and transparent elections, are not being adhered to” (Birikorang 2). The implementation of democratic constitutions, policies, and systems encourages freedom and equality, making repression and marginalization – the underlying causes of revolutionary violence and drivers of coups – less likely. derl

Sudan represents one of the many transitional democratic states in Africa whose recent history has been punctuated with instances of political violence. One of the reasons the country has been prone to successful coup attempts in the post-Cold War era is its lack of constitutional safeguards and judicial enforcement. This is perhaps best illustrated by the 1998 Constitution of Sudan, which, in adopting a form of so-called ‘Islamic Federalism’, did not sufficiently provide the safeguards and protections required to ensure that all citizens felt secure within the federal structure. Specifically, “…the 1998 Constitution does purport to enumerate certain freedoms, yet they are not absolute and are subject to legislative regulation. Moreover, their enforceability against individual states is unclear…” (el-Gaili 278). The constitution had recognized Sudan as a federal country, with a strong Islamic legal framework, but did not account adequately for the non-Muslim communities in the nation.

In addition, the constitution also lacked judicial support. The “Constitutional Court, a new institution established under the 1998 Constitution, offered little promise of upholding constitutional rights because it remained captive to the regime and its Islamist ideology” (el-Ghali 281). The implementation of a flawed and incomplete federal model which was unable to adequately address the divisions between communities in the North and South, contributed to the increasing tensions that ultimately resulted in the partition of the country in 2011. The enshrining of Sharia law as the basis of the constitution without adequate protection of the freedoms of non-Muslims marginalized those of other religious beliefs. The failure to develop an unambiguous and comprehensive Charter of Rights as part of the constitutional development process contributed to the sowing of divisions that remain obstacles to peace and stability today.

Conclusion

All in all, African leaders have failed to implement federalism effectively to prevent revolutionary violence on the continent. In some cases there has been a lack of the capacity and understanding required among actors to develop workable federal systems. In others, leaders have paid lip service to federal principles while engineering a state architecture which reinforces their own positions. The failure to develop federal structures which adequately meet the needs of diverse groups has contributed to ethnic division, interstate conflict, and political violence. Africans in many parts of the continent continue to struggle to live a democratic, fair, and free life. Notably, in Sudan the inability to constitute an adequate Charter of Rights and judicial system which guarantees true subnational autonomy, the use of federal models to sustain ethno-cultural division rather than accommodating it, and the consistent desires of political elites to maintain power, have inhibited the development of a peaceful, inclusive and democratic society. And, of course, these dynamics are not unique to the Sudanese case. Indeed, more broadly, similar deficiencies have contributed to the increase in revolutionary violence seen across the continent in recent years. In many African countries, including Sudan, actors have misused federalism as a tactic to preserve their school of thought, policies, and ultimately their influence. To avoid this it is important to pursue a decentralization of governance powers, to establish democratic legal frameworks, and to avoid constructing a state and governance architecture predicated on ethno-cultural difference. African leaders must recognize federalism a model underpinned by principles of pluralism. Engaging with civil societies on the ground to is crucial to including the voices of citizens in the development of federal and decentralized governance models which foster democracy and prosperity for all citizens.

Liam Whittington contributed to this article.

References

Bell, Curtis. “Coup d’Etat and Democracy.” Comparative Political Studies, vol. 49, no. 9, August 2016,p.1167-1200.HeinOnline, https://heinonlineorg.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/compls49&i=1136.

Birikorang, Emily. “Coup d’État in Africa – a Thing of the Past?” K O F I A N N A N I N T E R N A T I O N A L P E A C E K E E P I N G T R A I N I N G C E N T R E, 2013, media.africaportal.org/documents/KAIPTC-Policy-Brief-3—Coups-detat-in-Africa.pdf.

Chandhoke, Neera. “Can Revolutionary Violence Be Justified?.” Democracy and Revolutionary

Politics. : Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 95–116. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 12 Nov. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474224048.ch-005>.

el-Gaili, Ahmed T. “Federalism and the Tyranny of Religious Majorities: Challenges to Islamic Federalismn Sudan.” Harvard International Law Journal, vol. 45, no. 2, July 2004, pp. 503–546. EBSCOhost,

Gebeye, Berihun Adugna. “Federal Theory and Federalism in Africa.” McGill Law, 2019, https://www.mcgill.ca/law/files/law/2019-baxter_federal-theory-federalism-africa_berihun-gebeye.pdf.

Mbaku, John Mukum. “Threats to Democracy in Africa: The Rise of the Constitutional Coup.” Brookings, Brookings, 5 Nov. 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/10/30/threats-to-democracy-in-africa-the-rise-of-the-constitutional-coup/.

Mishra, Abishek. “Coups Are Making a Comeback in Africa, but What’s Driving Them?” Observer Research Foundation, 1 Nov. 2021, www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/coups-are-making-a-comeback-in-africa/.

Nichols, Michelle. “’An Epidemic’ of Coups, U.N. Chief Laments, Urging Security Council to Act.” Reuters, 26 Oct. 2021, 11:43 EDT, www.reuters.com/world/an-epidemic-coups-un-chief-laments-urging-security-council-act-2021-10-26/.

Powell, Jonathan, Trace Lasley, and Rebecca Schiel. “Combating Coups d’État in Africa, 1950-2014.” Studies in Comparative International Development, vol. 51, no. 4, 2016, pp. 482-502. ProQuest, https://login.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/combating-coups-détat-africa-1950-2014/docview/1846650560/se-2?accountid=14701, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9210-6.

Robbins, Michael, and Lawrence Rubin. “Sudan’s Government Seems to Be Shifting Away from Islamic Law. Not Everyone Supports These Moves.” The Washington Post, 27 Aug. 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/08/27/sudans-government-seems-be-shifting-away-sharia-law-not-everyone-supports-these-moves/.

V. Kostelyanets, Sergey. “THE RISE AND FALL OF POLITICAL ISLAM IN SUDAN.” Politikologija Religije, vol. 15, no. 1, Center for Study of Religion and Religious Tolerance, 2021, pp. 85–104, https://doi.org/10.54561/prj1501085k.