Anthony Bou-chrouche is a fourth-year student at the University of Ottawa, completing a double honours degree in Political Science and Economics. His research interests include international relations, financial econometrics, international finance, Canadian politics, and political philosophy.

For almost 50 years, Lebanon has been plagued with problems of civil unrest due to a lack of social cohesion that stems from religious differences among the groups that comprise its population. The country is home to 18 different religious communities, each of which possess constitutionally enshrined levels of representation in Parliament. In the legislature, generally seats are divided equally between Christian and Muslim communities (with some exceptions like that of the representation of the Druze community). Additionally, under Lebanon’s current political arrangement, various religious groups are entitled to specific forms of representation within the polity. For example, the President is required to be a Maronite Catholic Christian, the Speaker of the House is required to be a Shia Muslim, and the Prime Minister is required to be a Sunni Muslim. Given these constitutional requirements, Lebanon boasts one of the world’s most extensive forms of consociational democracy. However, despite this achievement, this system can often render decision making a more complex process in certain areas, sometimes leading to substantial delays in policy making. For example, Lebanon did not have a proper national budget for over a decade (2005-2017), as different sectarian parties were unable to reach an agreement [The Economist].

Many scholars have proposed that federalism could provide a solution to the governance challenges and policy making inertia currently facing Lebanon [Kéchichian & Cortez]. While in many ways Lebanon seems a perfect candidate for the establishment of a federal state, federalism alone may be unable to tackle the sectarian divisions within the country, and has the potential to add additional stresses to an already delicate fiscal management system. However, while there are undoubtedly challenges to implementing federalism in Lebanon, there are also aspects of Lebanon’s current demographic character and institutional practices that would lend well to the development of a federal state. This piece will explore both sides of the ‘federal Lebanon’ debate, and will seek to put forth an alternate argument for incremental change within the country’s current unitary system.

A Foundation for Federalism in Lebanon

Despite the current unitary system in Lebanon, aspects of the federal idea (such as different groups being allowed a certain level of autonomy in their decision-making process) are present in institutions such as the country’s court structure. The existing concepts and systems that align with federal principles could potentially ease future processes of transitioning to a federal model of governance. If Lebanon ever were to become a federal state, it would likely be a classic case of “holding-together federalism,” which includes processes of devolving certain powers to subnational units in the interests of national unity [Watts]. Following from this, from an institutional perspective solely, embracing the concepts of both shared rule and self-rule are unlikely to present a challenge in Lebanon. For example, the existing separation of religious courts in the country effectively already reflects the principle of different groups interacting with state institutions in varying ways, despite it not tackling the major issue of lack of willingness to live together. For example, family matters in Lebanon are resolved in religious courts. An eastern orthodox Christian, for instance, undergoing a divorce proceeding, will seek a ruling from his respective eastern orthodox court. Similarly, the children of a Sunni Muslim father will put forward their plea in front of a Sunni Muslim cleric to determine if the will of their late father ought to be respected depending on their individual family circumstances. All other cases are dealt with in national civil courts, but family matters are dealt with in that given citizen’s respective religious court. As such, different rules already apply to different people in Lebanon, despite it being a unitary state. Marriage rules are different for Maronite Christians compared to Shia Muslims, and so the notion of constituent units passing laws on behalf of specific communities is not all that unfamiliar for the average Lebanese person. This means that this specific aspect of federalizing – the principle that different policies and laws may apply to different groups in different parts of the country – is unlikely to generate significant political strife among the various Lebanese communities.

Additionally, those who support the idea of a federal Lebanon argue that it would allow the federal government, based in Beirut, to operate effectively without having to deal with the numerous problems associated with Lebanon’s current consociational democracy. If Lebanon were to adopt a federal system, it is conceivable that certain existing tensions within the country would be moved down to the state level, which may leave the federal government to operate with less religious interference. This in turn could help ameliorate the policy and legislative blockages and bottlenecks resulting from inter-religious tensions at the national level.

Challenges of Federalism for Lebanon

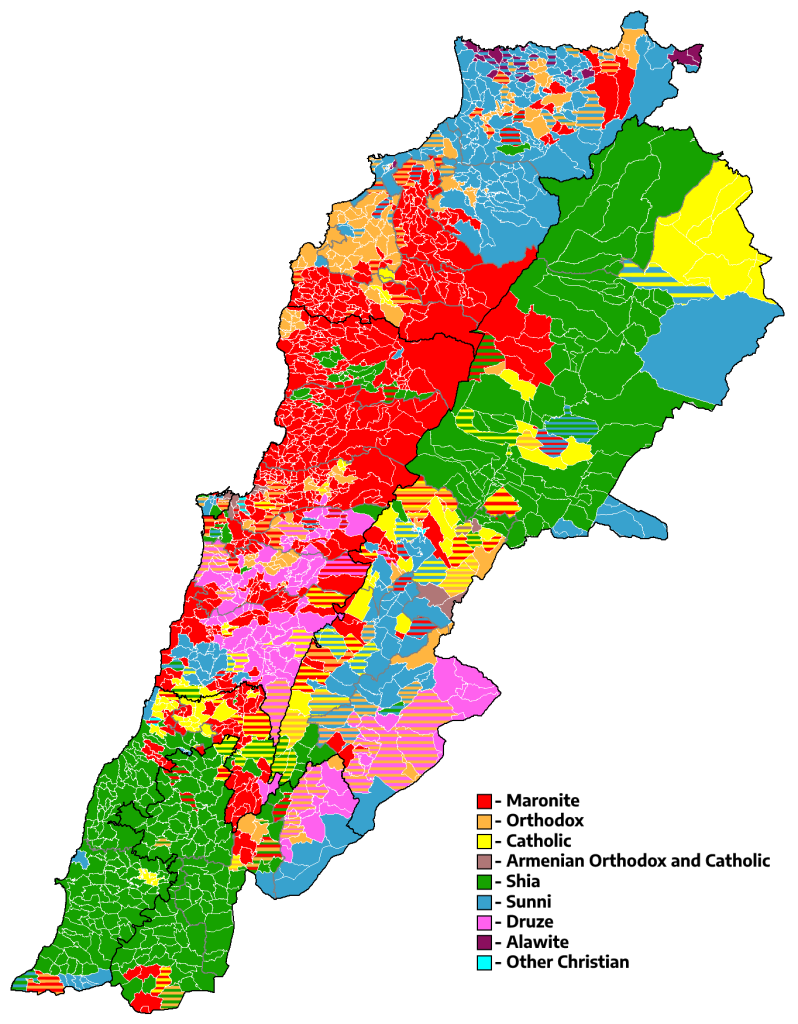

All federal states have constituent units with specific geographical boundaries. Such boundaries can be drawn based on linguistic, ethnic, or religious lines. In Lebanon, religion continues to be the greatest source of division between Lebanese people, so it is conceivable that the delineation of territory within a federal Lebanon may be based on religious lines. Though a federal system could be developed based on existing governorates of the country rather than on religious lines, this would not solve challenges stemming from the lack of will to live together that is posed by and rooted in religious difference. Another challenge is that there are no clear geographical lines separating religious communities in the country. Given this, the process of federalization may lead to the creation of new minorities within each new state – a problem that does not exist today and may lead to more conflict. The territorial distribution of religious communities in Lebanon is shown in the map below:

Author: Prodrummer619, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

As the map shows, the geographical division of religious communities is muddled in Lebanon. There is no straightforward way to delineate any specific area within which one religious community congregates. For example, the city of Beirut encompasses a territory of 19.8 square kilometers, within which people from all religious communities reside. Additionally, the demographic distribution has been further complicated by the recent arrival of around 1.5 million refugees from nearby conflict affected states, most notably Syria. This influx may further confound attempts to delineate new constituent units based on religious division, as there is no clear answer to the question of which religious community dominates in each geographic area. The challenge of territorial delineation of constituent units would be a significant obstacle in any federalization process in the country.

Even if Lebanon were to federalize, and territorial lines could be drawn, significant questions would remain concerning the devolution of powers to the states. While the assignment of these powers would almost certainly be negotiated in a constituent assembly (or a similar constitutional deliberation body), the process of negotiating the division of powers would be fraught if the current political divisions were to be replicated. In a federal Lebanon divided along religious or ethnic lines, allocation of powers could become highly politicized, although it is worth noting that in federations that are divided based on linguistic lines (rather than religious ones), deciding which powers ought to be handled by the constituent units can be more straightforward, especially in areas such as education. Additionally, a legitimate concern might be expressed by citizens who fear that the process of federalization might lead to the decay of the few healthy operational institutions. One such example is the health care system; Lebanon currently boasts an excellent healthcare system that provides fast and reliable services to citizens [Bloomberg Health Index]. If Lebanon were to federalize, great attention would need to be paid to ensure that any potential devolution of healthcare responsibilities to constituent units upheld the standards that Lebanese citizens have come to expect, and the same can be said about the education system.

Another challenge that a federal Lebanon would face concerns the expansion of the executive branch and civil service. The process of federalization often significantly increases the number of bureaucrats, civil servants, and political actors in a country due to the addition of multiple levels of government. Lebanon already has a large public sector, with roughly 230,000 employees in a country of approximately 5.4 million people [World Bank]. This disproportionally large public sector is due to many factors, most notably the existence of religious quotas within Lebanon’s bureaucracy. An example of this can be seen in the country’s railway industry. Despite the fact that the country has not had a rail transportation system since the beginning of the civil war and the trains have not been operational for decades, bureaucrats remain employed in this industry due to fear of retribution from the Shia community if they were to be let go [Hijal-Moghrabi]. These and other factors have contributed to drastically increased public spending, and the country is currently facing one of the worst economic crises since the mid-1850s [IMF]. If Lebanon were to initiate the process of federalization, the country would need to take steps to ensure that the expansion of the executive branch and bureaucracy does not exacerbate this situation.

An Incremental Alternative for Change

Though a prospective federal Lebanon would likely face a number of serious challenges, the country’s current consociational unitary system is also very dysfunctional. The problem lies not in Lebanon’s political system, but in the lack of willingness amongst Lebanese citizens to live together, largely as a result of the political manipulation of religious differences. Crucially, many Lebanese people fear that the separation of religion from the state as part of a governance reform process would lead to the loss of certain rights for religious communities. However, it is also clear that many conflicts and crises have occurred under the current governance system, which is not working. Therefore, rather than a federal revolution, some of the governance weaknesses may be alleviated through an evolution of the existing system. Working within and adjusting the current unitary framework, the introduction of additional institutional mechanisms to foster more inclusive decision making and citizen engagement in governance processes would be a more manageable and realistic first step towards addressing the disfunction that has plagued Lebanon for years. Two such mechanisms that could have a positive impact are national plebiscites and religious committees:

National Plebiscites:

Lebanon’s current unitary system may be improved by officially separating religion from the state, while simultaneously establishing a robust citizen engagement process in the form of national plebiscites on policy and legislation making. Such a process may be inspired by the successful practices found around the world (including in federal countries such as Switzerland), adopting an approach wherein if 10% of the population signs a petition within 50 days, the government holds a national plebiscite on that bill.

In the Lebanese context, this could potentially provide certain protections for religious groups (establishing a form of democratic veto) and may encourage politicians to consider possible retributions that may arise from ‘controversial’ bills. The implementation of such processes may lead to some form of consensus building among communities without this being an explicit constitutional requirement, and may assist in developing the level of harmony necessary among the constituent communities to foster national unity. Providing increased mechanisms for citizen engagement may assist in ameliorating concerns over ensuring the rights of minorities if Lebanon were to separate religion from the state.

Religious Committee to Declare War:

Lebanon’s geographical location in the Middle East, and its complicated internal political dynamics, makes it vulnerable to the geostrategic maneuvers of its neighbors. It is often drawn into external conflicts, whether it be through military action or internal political interference. The Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and militant group Hezbollah (deemed a terrorist organization by Canada, the United States, and the European Union), for example, has consistently used its religious ties and economic links with the Islamic Republic of Iran in attempts to push Lebanon into war with its neighbors. Oftentimes, these wars are as much about domestic politics as they are about the manipulation of religion to seek a given geopolitical goal. Yet, in the case of Lebanon, there is often very little consensus among the constituent communities to declare war due to the country’s confessional differences. In practice, the religious community that wields the most political power in Lebanon has been the one to call the shots on whether the country declares war on its neighbors. To prevent Lebanon from being dragged into conflicts outside of its borders, causing further fragmentation of Lebanese society, I suggest establishing a religious committee on the declaration of war, which would provide an institutional check and balance on external military action.

In this mechanism, each religious community would elect one member whose sole responsibility is to sit on a “War committee”, consisting of 19 members. Each of the (18) religious communities of the country would be represented by one member, encompassing all religious groups in Lebanon, with one additional member representing “Other” groups. The committee would only convene if the country was considering declaring war on a given organization or another country, but not in response to an ongoing security threat. The responsibility of the committee would be to vote on whether Lebanon declares war. A unanimous (binding) vote of the committee would be required for war to be declared. In a scenario in which Lebanon was not seeking to declare war, but was simply responding to a foreign aggression, the current security mechanisms may continue to be employed. This committee would in practice likely ensure that Lebanon almost always stays out of regional conflicts, because reaching a unanimous consensus among the various constituent groups is near-impossible, at least in the current political context.

Conclusion

Though Lebanon currently faces many challenges, it can be argued that many of the country’s problems stem not from its unitary governance system, but rather from the population’s lack of will to live together. One possible solution that has been proposed to tackle some of the challenges in Lebanon is federalism. Yet, while Lebanon may seem like fertile ground for federalism to thrive considering the diversity of the country and its various communities, a federal system based on religious lines may pose challenges due to the complex and multifaceted nature of the situation on the ground. The most prominent barrier remains the historic delineation of communities in the country that continues to influence the political process today. Given the complexity of the Lebanese situation, in order to foster national unity it may be beneficial for the country to adopt a more incremental approach to change (such as gradually separating religious groups from the unitary state) within the current unitary structure, with institutional mechanisms developed to ensure religious communities feel protected (such as a system of national plebiscites and a religious committee to declare war). One of the biggest challenges associated with federalizing based on religious lines is that it may simultaneously increase and decrease the autonomy of religious groups based on their geographic location, which may present further problems with minority recognition in newly formed subnational units. In this case, striking the balance between shared rule and self-rule that federalism necessitates may solve certain problems and create others for Lebanon.

Jamie Thomas and Liam Whittington contributed to this piece.

Bibliography:

Admin, BYJU. “Holding Together Federalism.” BYJUS, 12 Aug. 2022, byjus.com/ias-questions/name-an-example-of-holding-together-federalism/#:~:text=’Holding%20together%20federation’%20is%20a,the%20sovereignty%20of%20the%20country.

Bury, Yannick, and Lars P. Feld. “Fiscal Federalism in Germany.” SpringerLink, Springer International Publishing, 1 Aug. 2023, link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-97258-5_5#:~:text=The%20latest%20reform%20of%20Germany%27s,Laender%20and%20their%20parliaments%2C%20respectively.

Cortes, Francisco, and Joseph Kechichian. “Lebanon Confronts Partition Fears: Has … – Sage Journals.” Sage Journals, journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2347798917744292. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023.

“Why Lebanon Has Not Passed a Budget for 12 Years.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2017/03/27/why-lebanon-has-not-passed-a-budget-for-12-years. Accessed 15 Sept. 2023.

Hijal-Moghrabi, Imane. “Lebanese Bureaucracy.” SpringerLink, Springer International Publishing, 13 April. 2018, link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3549-1.

“Lebanon and the IMF.” IMF, 4 Aug. 2021, www.imf.org/en/Countries/LBN/faq.

Miller, Lee J, and Wei Lu. “These Are the Economies With the Most (and Least) Efficient Health Care.” Bloomberg.Com, Bloomberg, 19 Sept. 2018, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-19/u-s-near-bottom-of-health-index-hong-kong-and-singapore-at-top?embedded-checkout=true&leadSource=uverify+wall.

Nuffic. “Education System Lebanon.” Nuffic, 2016, www.nuffic.nl/sites/default/files/2020-08/education-system-lebanon.pdf.

Republic of Lebanon, Lebanese National Assembly. THE LEBANESE CONSTITUTION, 1929, pp. 1–24.

“Lebanon Government Debt to GDP2023 Data – 2024 Forecast – 2000-2022 Historical.” Lebanon Government Debt to GDP – 2023 Data – 2024 Forecast – 2000-2022 Historical, tradingeconomics.com/lebanon/government-debt-to-gdp#:~:text=Government%20Debt%20to%20GDP%20in%20Lebanon%20is%20expected%20to%20reach,macro%20models%20and%20analysts%20expectations. Accessed 8 Aug. 2023.

Watts, R.L. (2008) Comparing Federal Systems. Third Edition. Montreal & Kingston; McGill-Queens University Press. https://www.queensu.ca/iigr/sites/iirwww/files/uploaded_files/PDF%20Publications/ComparingFedSys3rd%2008.pdf

“Religion in Lebanon.” Wikipedia, 27 July 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_Lebanon#:~:text=The%20religions%20are%20Islam%20(Sunni,of%20the%20citizens%20in%20Lebanon.

World Bank. Lebanon Data. World Bank. 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/country/lebanon?view=chart. Accessed 06 November.